IgorSchwezoff - Master of the Ballet

IgorSchwezoff - Master of the Ballet IgorSchwezoff - Master of the Ballet

IgorSchwezoff - Master of the Ballet©1979 Scott Highton

Note: This story was originally photographed and written in 1979,while Igor Schwezoff was still living and teaching in New York city.

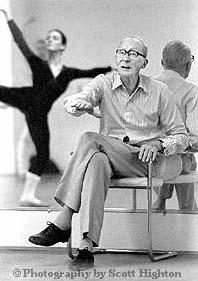

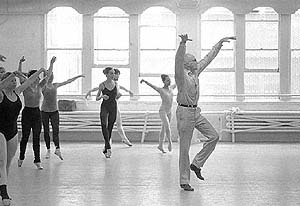

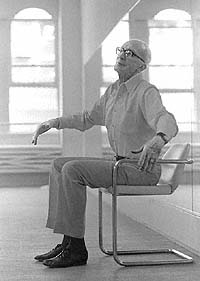

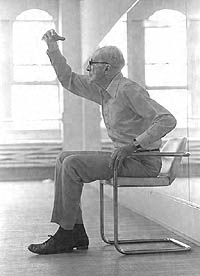

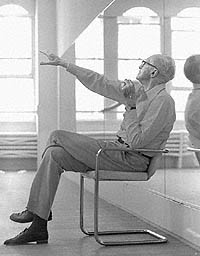

In a third floor dance studio overlooking a small street near New York'sLincoln Center, 25 men and women practice the graceful and strenuous exercisesof a ballet barre. Many of them are seasoned dance professionals, but foran hour and a half of the morning class, they will be under the close scrutinyand direction of an elderly gentleman sitting at the front of the studio.

Igor Schwezoff is a tall, slender man whose 75 years seem to have takennothing from his enthusiasm and love for ballet. He is calm and content,yet his eyes intently follow the movements of every student. Although heis virtually unknown outside the world of dance, many people within thatworld regard him as one of their greats, both as a dancer and choreographer.

Like many of today's ballet stars, Schwezoff was born and trained inthe Soviet Union and defected to the west in search of artistic freedomduring his prime as a dancer. The western world hails a long lineage ofgreat Soviet dancers, including names like Nureyev, Baryshnikov and Godonov.Their unrelenting spirit and often dramatic escapes from the Soviet Unionare legendary, yet despite their newsworthy drama, are following a trailblazed by Schwezoff and others half a century ago.

(Return to Picture Storyindex)

Schwezoff'sdefection came shortly after the Russian Revolution, which marked the beginningof governmental repression of creativity in the Soviet Union. He was oneof the pioneers, who risked all he had on one chance for freedom, and hewas one of the first to succeed. "An artist requires freedom to create"he said. "Otherwise, he is not an artist at all."

Schwezoff'sdefection came shortly after the Russian Revolution, which marked the beginningof governmental repression of creativity in the Soviet Union. He was oneof the pioneers, who risked all he had on one chance for freedom, and hewas one of the first to succeed. "An artist requires freedom to create"he said. "Otherwise, he is not an artist at all."

Now, half a century later Schwezoff still feels that he has found thefreedom he sought and has utilized it to its fullest. Although he retiredfrom dancing in the mid 1940's, he has been actively choreographing andteaching throughout the world since. Today, he lives in a large apartmentnear Central Park in New York and teaches one class a day for professionalsat the New York Conservatory of Dance.

Still speaking with a thick Russian accent, Schwezoff talked of his owndefection and those of more recent Soviet stars. "Defectors now arewelcomed with open arms by western countries" he said. "When Iescaped, I was called a communist and considered a pest wherever I went.At the time, I couldn't even get a passport or working papers."

(Return to Picture Storyindex)

In 1934, Schwezoff won a prize for the best English language autobiographyoffered by Hodder and Stoughton Publishers in London for his autobiographyentitled Borzoi. In the book, he described his youth, his introductionto ballet, life in Russia during the revolution and his remarkable journeyto freedom. He said "I wrote the book because I felt there was a needfor people to know what the people in the Soviet Union went through duringthat time."

Even now, Schwezoff admits that he led a rather spoiled childhood inthe pre-revolution era. His father was a genera in the Imperial Guards andhis mother was the daughter of a rich banker. "She brought wealth tothe family, and he brought rank" he wrote. "I was a proud, difficultboy, and from childhood on, had never allowed anyone to tread on my feet.I always had a certain kind of respect from people the kind of respectone gives to a cactus."

During his teens, Schwezoff was introduced to classical ballet and decidedto take it up as a profession. He established himself as an excellent danseuramong the many companies and other dancers in Russia. However, after therevolution and the ensuing government takeover of the theater, he beganto have difficulties with the managements of some of the companies he workedwith.

"Because I thought of art as art, and not as communist art nor evenas communist propaganda, I was persecuted. I was actually indifferent topolitics of any kind. I only shared the disposition common to all artiststhat an artist is only an artist by virtue of his intensified individualism.A communist artist is actually a contradiction of terms.

"The grandeur of the Soviet theater" he continued, "liesin the fact that it has become what it is, not because it is a vehiclefor communist propaganda, but in spite of it."

Foryears, Schwezoff endured the the miseries of life in Russia during the post-revolutionera. The communist government had taken away the great wealth of his family.Those who were still alive lived a meager day-to-day existence. His motherhad died from an illness. His oldest brother was a political exile who waslater presumed dead, and his father was hiding from the new regime. Schwezoffand his younger sister survived by living in the bathroom of a small flatin Leningrad. It was the only place they could find warmth during the coldRussian winters. Despite the many hardships, he continued with his studyof ballet, and started developing his reputation as a fine dancer and choreographer.

Foryears, Schwezoff endured the the miseries of life in Russia during the post-revolutionera. The communist government had taken away the great wealth of his family.Those who were still alive lived a meager day-to-day existence. His motherhad died from an illness. His oldest brother was a political exile who waslater presumed dead, and his father was hiding from the new regime. Schwezoffand his younger sister survived by living in the bathroom of a small flatin Leningrad. It was the only place they could find warmth during the coldRussian winters. Despite the many hardships, he continued with his studyof ballet, and started developing his reputation as a fine dancer and choreographer.

Years later, while on tour with one of the Russian Ballet companies,he seized an opportunity to escape. Unfortunately, what was to be only athree-day trek across the frontier to freedom in China, turned into a harrowing,month-long journey for Schwezoff and a few companions. During their ordeal,they were captured and escaped from border patrols, nearly froze to death,and lost their few valuables along the way in trades for guides, food andplaces to hide.

In Borzoi, Schwezoff tells how, with only the clothes on his backand ballet shoes on his feet (he accidentally burned his boots one nighton the trek while trying to dry them), he reached freedom in China. Thiswas in November, 1930. His troubles were not over though, as he was a completeunknown in the dance world outside the Soviet Union. The task of provinghimself to the rest of the world still lay ahead.

Several months later, however, he arrived in Paris to dance with theOriginal Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. After a short time there, he wentto Argentina and the National Theater of Buenos Aires, where he worked underthe direction of famed Russian choreographer Michael Fokine. When Fokinesaw Schwezoff dance in Argentina, he immediately promoted him from corpsde ballet to first dancer. Schwezoff's steps to freedom seemed to finallyhave paid off.

Inthe following years, he worked with Madame Nijinska in Paris and openedhis own successful studio in London. His work as both dancer and balletmaster of a new company in Amsterdam was so successful that he is todayconsidered one of the founding fathers of the dance movement in Holland.

Inthe following years, he worked with Madame Nijinska in Paris and openedhis own successful studio in London. His work as both dancer and balletmaster of a new company in Amsterdam was so successful that he is todayconsidered one of the founding fathers of the dance movement in Holland.

For several years, Schwezoff again worked with the Original Ballet Russe,both as a dancer and choreographer. In 1945, he was granted citizenshipin the United States, after having served briefly in the US Army. Then,at the age of 41, he retired from dancing to devote all his time to choreographingand teaching. That year, he became the artistic director of the NationalTheater in Rio de Janero, where he choreographed and produced a remarkable13 ballets in nine months.

Subsequent years brought Schwezoff back to the United States, where hetaught at the American Ballet Theater in New York. In 1961, he moved toWashington, DC to teach at the Washington School of Ballet. A short timelater, he opened his own studio nearby. Over the next five years, he dividedhis time between his Washington, DC studio and both the Asami Maki BalletCompany and the Tachibana Ballet School in Tokyo.

A long illness forced him to close his Washington studio, so he returnedto New York where he taught with the Harkness Ballet Company, The MetropolitanOpera Company and the Youskevitch Dance Studio. Now, at age 75, he has limitedhimself to teaching one class a day at the New York Conservatory of Dance.

(Return to Picture Storyindex)

Schwezoffspoke in his apartment one afternoon about his long career, his love ofballet and his teaching techniques. His apartment is quite large and hasa distinct flair of Russian aristocracy about it, perhaps similar to thesurroundings in which he grew up. The walls are lined with photographs andpaintings of old Russia, as well as pictures and drawings of himself, givento him by students and friends. The busy sounds of West 72nd Street severalfloors below drifted up through the open window.

Schwezoffspoke in his apartment one afternoon about his long career, his love ofballet and his teaching techniques. His apartment is quite large and hasa distinct flair of Russian aristocracy about it, perhaps similar to thesurroundings in which he grew up. The walls are lined with photographs andpaintings of old Russia, as well as pictures and drawings of himself, givento him by students and friends. The busy sounds of West 72nd Street severalfloors below drifted up through the open window.

"There are two basic elements to classical ballet" he said."They are quality and quantity. Quantity is how much a dancer can physicallydo, while quality is how he or she does it. The two elements must alwaysgo hand in hand.

"Quality is the most difficult phase in the development of an artist,and requires long and arduous training. It is the element that gives finishand significance to a dancer's movements. Quantity however, is the elementthat gives an artist the freedom to concentrate on quality. If you havethe ability to do many skills and movements, then you can stop worryingabout doing them and concentrate on the expression and quality of movement.

"The technique and amount of impressive skills are only secondaryin classical ballet" he said. "It is the expression by the dancerwhich is most important. Being able to do many tricks and dancing are twoentirely different things. Art is not just being able to do 102 fouettésor 35 entrechats in the air, nor is it the number of pirouettes, tours deforce or acrobatic tricks that a dancer can do. Art is more than that.

"Some dancers have the facility for tremendous beats, jumps andturns, but that doesn't mean they are good dancers yet. Classical dancingis something more. It involves the quality of movement. Take forinstance, Natalia Makarova. She is not a strong technician, but when shecomes on stage, she has a quality of movement which absolutely takes theaudience in." He added, "the more difficult the movements a dancerdoes, the easier he or she should make them look."

In an article Schwezoff wrote on the subject of quality and quantity,he said, "personally, I do not believe in art that does not conveyto one some feeling. Art is not something nice, sweet or pretty. It is morethan that. Art is something vital. It may be beautiful or even hideous,but it must be deep and strong in its expression. Art is not, and shouldnot be mechanical. It must always be alive."

Schwezoff emphasized that quality by itself is also not enough to makea good dancer. "Emotion alone is not sufficient, and in fact, is badin dancing," he said. "Emotion has to be controlled. Until thedancer is the full master of his body and is well able to control his emotions,he is neither able to display them to full advantage, nor is he able toconvey these emotions to the audience. The stronger one's technique, theeasier one is able to devote oneself to the emotional and artistic sideof dance. This is the reason why in class, one often does exercises andsteps far more difficult than one will ever dream of performing in frontof the public. The development if the body is required in order to be ableto exercise more control over emotions."

Withhis emphasis on the importance of both expression and strong technique,one would rightly believe that Schwezoff's dance classes would be difficultand demanding. This is confirmed by the exhausted dancers collapsed ontochairs and benches outside of the studio after class. Schwezoff himselfeven admits that his classes are difficult.

Withhis emphasis on the importance of both expression and strong technique,one would rightly believe that Schwezoff's dance classes would be difficultand demanding. This is confirmed by the exhausted dancers collapsed ontochairs and benches outside of the studio after class. Schwezoff himselfeven admits that his classes are difficult.

"For the first half hour or so, I give a strong barre to get themwarmed up" he said. "Then, for the remaining hour, they move tothe center of the studio where I give corrections on movements and sequences.Occasionally, I give a completely different movement to let them throw themselveslike crazy up and down. I try to get them to use what they've learned. Otherwise,they get stiff and forget what dancing really is." The students arenot the only ones who are tired after one of Schwezoff's classes. "Atmy age" he joked, "one class is about all I can take in a day."

In his writings, Schwezoff previously said "the teacher should trainhis pupils to use their bodies not only to be mechanical instruments, butto live, vibrate and respond to the mood an rhythm of the music. My pointof view is that if one has a perfectly trained body, it should be able toexpress anything and speak for itself in movement."

Schwezoff said that he has only seen one "perfect" dancer inhis life Olga Spessiva, another Russian who was a star of the ParisOpera Company. "She was perfect in every aspect of dance... her technique,lines, movement, everything. I danced with her while I was in Argentina.She was absolutely marvelous."

When asked if he thought of himself as a perfect dancer, Schwezoff quicklyreplied "no, I never was. I was too tall and too long. That was a handicap.People liked me very much because it was beautiful to watch such long movements.I looked very good because I was so tall and was able to cover up poor technique,but no, I was never perfect."

Despite his imperfection, Schwezoff has still met with many successesthroughout the world. Yet, he is not nearly as well known nor recognizedas many other ballet greats. That fact seems to strike a slightly sour notewithin him. He explained "in order to be well known, you have to bepushy. I was always spoiled because I never had to ask for a job. They werealways offered to me. I was not pushy enough when I was young" he said,"and I am too old to be pushy now."

"Had I stayed in the Soviet Union, I probably would have been moresuccessful, because I think in the United States, I am not much appreciated.However," he was quick to add, "I am quite glad that I left. Ihave been very satisfied with the places I have been and the work I've done."He did add, "I wouldn't mind going back for a visit sometime, though."

Looking back on his reasons for leaving Russia, Schwezoff summarizedhis feelings. "I left because I would always be watched. They toldme that I had no future, that I would never be trusted by the managementof a company so that I would never have a free hand to choreograph as Iwished. If you had an idea there, it always had to be approved and mustalways include a touch of communist propaganda.

"That is why dancers and artists are still defecting from the SovietUnion" he said. "They are artistically dissatisfied because theyhave to do old ballets that they don't like and there is not much creativityin the companies. Maybe now, after the more recent defections, the Sovietswill pull up their artistic level. They'll have to. Otherwise, they'll continueto have more and more artists defect."

But what about the artists that have already defected? Will they findthe freedom that Schwezoff has found? Will they be as satisfied with theiropportunities outside of their homeland as he has been? "Yes,"said Schwezoff with a smile, "I suppose they probably will."

Epilogue

In the early 1980's, several years after this story was originally written,Igor Schwezoff died in New York. He never did get the chance to return tohis Russian homeland or to see the collapse of the former Soviet Union,which occurred shortly after his death.